- Home

- Richard Unekis

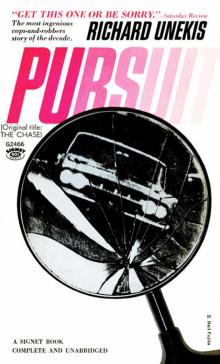

Pursuit Page 3

Pursuit Read online

Page 3

The echoes of the scream died away. His raw reaction subsided. He became aware that he was still sitting at his desk in the hubbub of the busy store, and that the man on the phone might demand something to save his child’s life.

The two cashiers, blissfully unaware, were still busily cashing checks, tending the two lines of women.

Again there was the insistent voice coming from the phone: “By God, answer me or you’ll be sorry. Do you hear me, Fairmount?”

He fought down his nausea enough to croak: “Yes, yes, I’ll do anything you say. Please don’t hurt her any more. Please!”

“Keep your voice down, you fool,” was the reply. “Remember, I told you if you sick the cops on me, it’s the end. That goes for their coming out here by accident, too, so be careful.” He paused, then continued, “Listen good, now. First, I want you to sit right where you are and count to twenty-five—to yourself—then tell me if you’ve got yourself under control enough to do what I say without giving yourself away.”

After a pause of perhaps a minute, the pale-looking man said into the phone: “Okay.”

“All right, where’s the money?”

“In the safe.”

“Can you get it? Is there a time lock?”

“No, no time lock, just a combination.”

“Open it, and tell me when it’s done.”

Rising, he noted the back of his trousers was stuck to the chair. He wondered dimly if he had urinated. It was funny, but it seemed absolutely unimportant at the moment. The only important thing seemed to be Cindy.

He knelt and fumbled at the safe. His fingers trembled. Finally, on the third try, it came open.

He went back to his desk. On the way he glanced up at the row of checkers to see Mollie looking at him peculiarly. He looked quickly away. “Oh, God, don’t let her interfere,” he prayed desperately.

“It’s okay,” he said into the receiver.

“Is it still in the bag they brought it in?”

“Yes.”

“Now get this. In a couple of minutes a man wearing the same uniform as those guards is going to come in. He will stand at the door of your office, the one between the cashiers’ windows. You will take the sack from the safe and hand it out to him, in view of everybody. Do you understand?”

“Yes.”

“If any employee questions you, say, ‘I’m the manager here. What do you mean?’ Say it indignantly. Can you do that?”

“I—yes, yes, if I have to.”

“You have to. Do you know what will happen to your little girl if you fail?” The voice took on its cutting edge again.

“Please, please don’t.”

“Shut up! After he leaves, I want you to go into the toilet. Stay there for exactly ten minutes. Then come out and sit at your desk. Act busy and talk to no one. I will call you and tell you when I leave. Don’t call at all back here. If the cops come out here before I call you and tell you that it’s all right, you know what’s going to happen to your family.”

The line went dead.

12

Grozzo’s left arm was beginning to get cramped, holding down the receiver hook, but he was too tense to be very aware of it. For some crazy reason he began to feel almost as if he were hanging from a cliff as he stood there waiting, waiting, waiting for the phone to ring.

At last it did ring, jarring away his feelings, snapping him to alertness. He released the hook, and said “Yeah?”

“It’s all set—go—don’t waste any time.” Rayder’s voice was tense.

Without replying, the swarthy man cradled the receiver and walked rapidly to the car. He drove it to a point near the store’s door, but off to one side, out of the line of vision of the office and checkout counters. Leaving the engine running, he put on the uniform cap and started walking toward the door. After a few steps he realized he was going too fast, and checked himself to a deliberate stride.

He was nervous now, in spite of himself. His palms were wet. As he stepped on the rubber mat before the door, there was a loud hiss. He jumped in wild alarm. It was only the automatic door opener.

He stepped into the air-conditioned interior, somehow expecting all hell to break loose as he did so, or at least to find everyone staring at him. He was surprised when no one even looked up. The busy clatter of the checkout counters continued without pause.

As he stepped over near the office door, the manager looked at him through the glass partition with glassy eyes and a pale face. He felt a little reassured. From the look on the manager’s face, Rayder had softened him up good. He gave a small nod, and the man stood up and went to the safe.

He took a quick look around. The two cashiers on either side of him were curious at his standing there between the lines of waiting women. One of the checkers was really curious, glancing rapidly around between stabs at her cash register.

The clock on the wall read 10:35.

Suddenly, the other man was handing him the heavy sack. He nodded quickly, then turned to walk the twenty steps to the door.

It was the longest walk he had ever taken.

With every step he expected to hear a scream, a gun, an alarm—or to feel something hit him.

Nothing happened.

Nothing at all.

As the automatic door swung shut behind him, he could hear the uninterrupted rhythm of the store, until the heavy glass shut it off, and he was alone again in the heat.

Alone with the heavy sack.

He wrestled down a tearing urge to run. It seemed like a mile to the car. His nerves, his every instinct, screamed at him to get away, GET AWAY, FAST, FAST, FAST! He had a wild impulse to pound the throttle and send the car screaming across the lot and down the highway.

Grinding his teeth until he felt a filling break, he smothered the impulse and smoothly feathered the car out of the lot and down the lane toward Fairmount’s house.

13

As the hawk-nosed man put down the phone again, he whirled, pointing at Mrs. Fairmount. “All right, there’s not much time. Get on that couch.” Her eyes opened wide in fear. Immediately sensing the cause, he said, “No, not that, damn it, I’m not going to hurt you.”

He produced a roll of wide adhesive tape, and after making her lie on her stomach with her hands behind her back, he taped her wrists together, then her ankles. Next, he put a broad strip across her mouth.

Looking down at her, he said, “You’ll be all right till somebody comes. Just don’t struggle around and make yourself sick so that you vomit, or you’ll choke to death.”

He did the same thing to the sobbing, hiccuping little girl, first laying her on the floor.

Next he took from his pocket the small metal box he had brought from the car, on which was mounted a little spool of plastic tape. From one end of the box, he pulled two wires out to about an eighteenth-inch length. A metal clip was attached to each one. Taking a penknife, he cut back some of the covering on the telephone line which coiled from that instrument down to the wall, then snapped one clip to each of the exposed strands. He set the box on the desk.

After this he took out his handkerchief and went rapidly around the room, and then back over the route he had taken into the house, wiping every hard surface he had touched. He seemed to have made a mental note of them.

Finally, he returned to the den and looked in, as if surveying his work. The little girl was hiccuping quite badly between her sobs. He listened and looked at her for a few minutes as if weighing something. Then he went over to her and stripped the tape from her mouth.

Half defensively, he said to the prostrate woman, “Don’t want her to choke if she vomits.”

It was the only time he had come close to exposing any emotion other than constant icy composure.

He walked down the half-stairs, and down the hall, then stood by the front door and waited until the blue and white car appeared. He walked briskly down the sidewalk to it and climbed in. The car turned the corner down the subdivision’s access road, and then moved off

into the network of county roads. It proceeded east until it came to the road the men had reconnoitered in the morning. Then it turned south toward Bucola, accelerating rapidly.

With the speedometer needle quickly climbing to 70 on the gravel road, loose rocks thrown up by the wheels began to drum a steady tattoo against the floorboard of the car.

Rayder quickly jumped into the back seat to tune in the local police frequency on the short-wave.

Grozzo began to count the crossroads as they came up, an even mile apart.

He had got up to five when he noticed a fluttering object cross the field of vision high and to the west of them. He had just turned around to tell Rayder there was a blue helicopter in the sky off to their right when, with a crack like a rifle, the left front tire blew.

14

As the stocky man in the guard’s uniform went out the pneumatic door, George Fairmount walked, rather unsteadily and with his head down, back to the men’s room.

The two cashiers paused to exchange wondering, curious glances, then turned to continue their work. The dawn of suspicion pressed upward in their minds, but they would not let it come through—not yet. Something more would have to happen before they would be able to admit to themselves that something threatening might have happened. Something definite. Something so real and immediate that they could not possibly refuse to see it.

Not so with Mollie. She was beside herself trying—unsuccessfully—to get a look at George’s face as he slouched past.

Her curiosity infected one or two of the other checkers momentarily, a few feet away from the scene of action, but they had all been too intent on their work to have caught the little byplay at the office. The lines of shoppers moved steadily through to the continuing staccato of the registers.

George did not stay in the toilet ten minutes. He tried, but he could not force himself to stay more than a couple of minutes. When he came back and sat at his desk, his head was still down.

Shifting in his chair so that he could see the clock on the wall, he stared at it. He put one hand on the phone and left his back turned to the row of checkers, waiting for the promised call.

The clock went around to 10:45. It was ten minutes. The phone did not ring. His face showed more strain.

Mollie could stand looking at the back of his neck no longer. She said “Excuse me” to an indignant fat lady as she stopped counting in the middle of an order and walked around to the office.

“Is something wrong, boss?” she started, then stopped. One close-up look at his pasty, scared face, as he turned toward her, told her plenty was wrong.

He said, “No, nothing’s wrong, go back,” and waved vaguely toward the row of checkers. He went back to staring at the clock.

Mollie walked back toward the rows of shoppers, hesitated only a second, then walked rapidly on around them and out the front door.

15

Superintendent Franklin stood looking out the front door at the men standing at attention in the hot sun, awaiting the helicopter.

He had just put out his hand to open the door and go out and put a stop to the foolishness when the phone rang. Pausing with his hand on the knob, he waited while the operator answered. As the man listened, his face paled. He looked up quickly. “Robbery in progress, Riteway Supermarket at Dale Shopping Center.”

“Robbery in progress” is as much an automatic alarm signal to a policeman as the gong for General Quarters is to a sailor. Franklin yanked open the door and took the steps at a jump, yelling “Inspection is off, robbery in progress.”

“Sergeant,” he said to the astounded man, “in there, on that radio.” He sprinted down the row of cars and men until he came to the last four. “You men come with me,” he shouted.

He jumped into the last car, told the driver where to go, and pulled the mike from the dash. “Sergeant Catlin,” he said. There was a short pause, and the reply, “Yes, sir.”

“We have a ‘robbery in progress’ at Riteway Supermarket, Dale Shopping Center. I have four men with me. Contact the local force and the Sheriff’s office.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Also, you’d better move your force off the lot there. Get them out and moving so we don’t get jammed up.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Okay, and stay close to your transmitter.” He hung up the mike.

16

At 10:48 George Fairmount was unable to stand the strain any longer. He dialed his home.

He did not even hear the phone ring, before it was answered. He started to say, “Honey, are you all—”

The man’s voice came on, even more harsh than before, cutting through his own. “Damn you, I told you not to call back here, that I’d call you. This is your last warning. Don’t try it again.”

With trembling hand, George hung up the phone, then buried his face in his hands and sobbed uncontrollably.

He did not see a State Police car come to a fast, bouncing stop in front of the store, closely followed by three more. The officers leaped out and walked rapidly toward Mollie, who went up to meet them. They stood in front with her for a few minutes, talking rapidly. Then they came into the store.

The officer in charge walked up to the office. The other four stayed back in a half crouch, near the door. Their right hands were atop their holsters. Their glances walked rapidly over the store, looking for trouble.

The first man, in plain clothes, stepped through the still-open office door. George looked up, his eyes red.

“Sir, I’m Superintendent Franklin, State Police. What’s wrong here?”

George paled.

“Nothing,” he said. “Nothing’s wrong, go away.”

“Have you been robbed?” Franklin persisted.

The two cashiers gasped.

One by one, as they became aware something was going on, the checkers stopped working. The steady medley of the cash registers dwindled and stopped. Checkers and customers stood gaping.

George writhed under the Superintendent’s firm gaze. “Just go away, please. It’s all right. There’s nothing wrong.” His voice was pleading.

Franklin was obviously convinced otherwise. He beckoned one of his men.

Before the man could get there, the phone rang. Putting his hand over the manager’s phone, Franklin said, “I’m taking all calls.”

“No. Please! Please let me take it,” George almost shouted, then finished lamely, “I—I’m expecting an important long-distance call.”

Franklin said, “Wait.” He stepped over to the cashier’s window and put his hand on the phone, then said, “Are these phones on the same line?” One of the cashiers nodded meekly and said “Yes.”

Franklin nodded to the other man, and picked up his phone at almost the same instant as George did.

An excited woman’s voice came on: “… George? George, this is Madge, George, I think there’s something wrong at your house. A man was there a long time, but he left. Then, when I tried to call, a terrible man answered and cursed and said that he told me not to call back, and I thought I had the wrong number, so I called back, and he told me exactly the same thing again. I’m scared. I—”

Franklin broke in. “Lady, this is the police. Let me have your name and address, please.” He scribbled it down as she talked, then turned to George. “How much did they get?”

George floundered for a minute, then collapsed. “All of it,” he faltered. “Eighty-five thousand, but don’t do anything, please. They’re at my house. They’ve got my family out there. He told me he’d call and tell me when they were leaving. Please wait. Please!” Tears stained his puffy cheeks. His eyes were red and swollen.

Franklin dropped his gaze, then turned to the officer nearest him. “Get on the radio and tell Sergeant Catlin we have a confirmed eighty-five-thousand-dollar robbery here, tell him to put an alert on the state wire, and tell him we’ll try to get a description.”

He turned back to the distraught man. “What’s your home phone number?” Then he said, “No, wait, y

ou call so they won’t get suspicious if they’re still there.” He motioned to the phone.

George dialed, with the officer listening. The same voice came on and repeated the previous warning. Halfway through, the manager suddenly hung up and cried hysterically, “That’s the same one. He said just exactly the same thing as the other time I called.”

“Exactly the same thing?”

“Yes.”

“Dial it again.”

“No, no, no!” George ran from the office, toward the back of the store.

The officer turned to one of the petrified cashiers. “Dial his number.”

She complied.

The voice came on again. Before it had said ten words, Franklin hung up.

“That’s a tape!” he shouted. Turning to two city policemen who had come in, he said, “You two get out there fast. Find out what you can.”

Another local car came screaming onto the apron and screeched to a stop. Two officers bolted in. Franklin intercepted them, and gave them a piece of paper.

“Find out who or what this woman saw going into or out of George Fairmount’s house this morning. Radio in any descriptions you can get.”

He turned back to the cashier who had placed the call for him. “You were right here. What did you see? What did they look like?”

She dissolved into tears.

Grimacing his impatience, he looked around.

Mollie came up and said, “I saw him. There was just one. He had on a guard’s uniform like the guards who deliver the money. He was kinda short and heavy and dark. He had black hair.”

“Only one?”

“Only one,” she repeated.

“What did the car look like?”

“I didn’t see any car. He walked around the corner after he left the building.”

Franklin’s face was grim. “Okay,” he said. “Stick around.”

He phoned his information in, then went toward the back of the store for George. Bringing the almost incoherent man back to his office, he tried, unsuccessfully, to question him.

Pursuit

Pursuit